Besprechung auf Deutsch-Review also in English-Reseña también en español!!

Die Frage nach dem Exportschlager der Philippinen wird von ihnen selbst häufig beantwortet mit: „Unsere Menschen“! Diese Antwort hat einen realen und dramatischen Hintergrund. Nach Schätzungen arbeiten von den etwa 120 Mio. Filipinos rund 10 Millionen, mehr als die Hälfte davon Frauen, im Ausland, die Mehrheit dieser „Overseas Filipino Workers“ in anderen asiatischen Staaten, in arabischen Ländern, den USA und Kanada.

Auslandsüberweisungen sind ein für die Philippinen unverzichtbarer Wirtschaftsfaktor, sie betragen rund 10 % des Bruttoinlandsprodukts (etwa 40 Mrd. US-Dollar). Für viele Familien bilden diese Zahlungen ihre unverzichtbare Überlebensgrundlage.

Der Preis für die Menschen ist hoch. Väter und Mütter sind von ihren Kindern oder Ehepartnern, anderen Familienangehörigen und Freunden getrennt, und das vielfach über Jahre hinweg. Die Arbeits- und Lebensbedingungen in einer Vielzahl der aufnehmenden Staaten sind alles andere als menschenwürdig, Ausbeutung, um nicht zu sagen eine moderne Form der Sklavenhaltung sind an der Tagesordnung, die Grenze zwischen Arbeitsvermittlung und Menschenhandel sind fließend, es gibt viele Reisen ohne Wiederkehr…oder der Wiederkehr in einem Zinksarg.

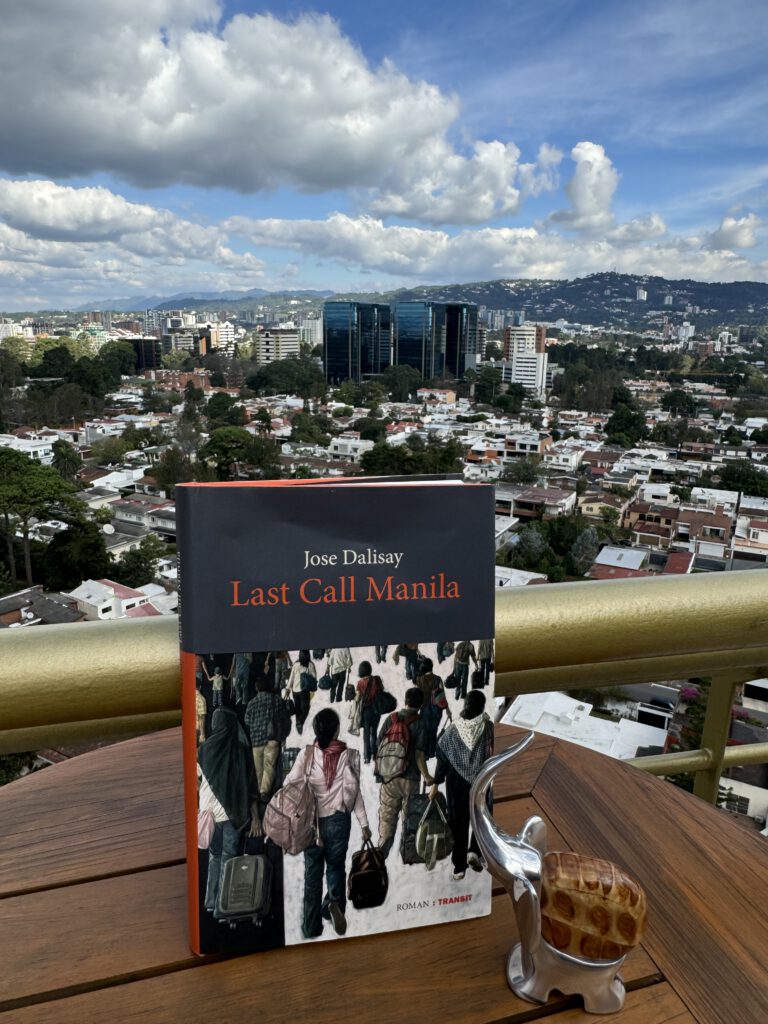

Dieser für die Philippinen alltäglichen Realität widmet sich der Roman „Last Call Manila“ von José „Butch“ Dalisay.

Aurora V. Cabahug ist eine dieser jungen Frauen, die im Ausland ihr Auskommen suchten. Sie kehrt nach Manila zurück – in einem Zinksarg. Aurora hat jedoch „Glück“. Der mit der Suche nach der Familie beauftragte Polizist Walter fällt beim Lesen des Namens aus allen Wolken. Aurora Cabahug? Rory,die Sängerin? Die hatte er doch am Abend vorher noch bewundert? Und in der Tat, Aurora ist quicklebendig. Walter, heimlich verliebt in die attraktive Sängerin, fährt mit ihr die stundenlange Strecke in die Hauptstadt Manila, um den Sarg mit der ihm unbekannten Toten abzuholen und enthüllt so Kilometer um Kilometer deren Geheimnis.

Aurora und ihre ältere Schwester, wie fast alle Filipinos mit spanischem Namen, Soledad (bezeichnenderweise: Einsamkeit), sind Überlebende einer familiären Katastrophe. Als besonders nah kann man ihr Verhältnis dennoch nicht bezeichnen: „Soli war, um ehrlich zu sein, immer mehr ein Dienstmädchen, als eine Schwester für sie gewesen, und es ist schwierig, jemanden zu vermissen, der ebenso ein Fleck auf einer weißen Wand hätte sein können“.

Soledad war bereits vor Jahren nach Hongkong aufgebrochen und später mit einem Kind zurückgekommen. Den Kleinen ließ sie sehr bald alleine bei ihrer Schwester Rory, und borgte sich deren Identität, um sich eine berufliche Zukunft in einem arabischen Land aufzubauen. Es bleibt im Dunkeln, was mit Soledad in diesem Land geschehen ist, es interessiert dort auch niemanden. Sofern es sich bei Toten nicht um Mitglieder der königlichen Familien oder andere Einflussreiche handelt, werden sie nach drei Tagen weggebracht: „Einfach so?“ – „Einfach so“.

Auf dem langen Weg nach Manila erfährt man nahezu beiläufig Einiges über die Philippinen. Sei es über die komplexen Strukturen einer tief verwurzelten Korruption, sei es über die immense Binnenmigration aufgrund fehlender beruflicher Perspektiven: „Menschen, die eigentlich nie ernsthaft eine Chance hatten, die nur widerwillig akzeptierten, dass jeder Tag, an dem man drei Mahlzeiten im Bauch hatte, ein guter Tag und das alles, was darüber hinaus ging, ein Segen war, der bewahrt und verteidigt werden musste vor der ständigen Gefahr, vom Glück verlassen zu werden“.

Oder sei es über die noch immer existente Links-Guerrilla: „Einige Leute trugen Waffen, die weitaus größer waren als seine 38 er Dienstwaffe. Es waren Handlanger und Anhänger eines verbissen Glaubens an – was war es noch mal? – Gerechtigkeit oder die Zukunft oder irgend so eine Abstraktion, die niemals eine weitere Leiche mit offenem Mund und von Fliegen befallen, irgendwo in einem Graben, rechtfertigt“.

Es fehlt auch nicht an realkomischen, die Mentalität der Filipinos widerspiegelnden Szenen, wie die Familie, die zu früh zum Abholen eines in einem arabischen Land enthaupteten engen Angehörigen kommt und sich dann bis zum nächsten Tag auf einem nahen Volksfest vergnügt. Das Leben ist kurz.

Von der großen Überraschung des Identitätstausches abgesehen, gibt es auch andere Volten in diesem Buch, die trotz aller Tragik wegen ihrer Absurdität wieder eher zum Lachen sind. So wird der Wagen mit dem Sarg von einem Kleinkriminellen gestohlen und verschwindet mit diesem im Brackwasser eines der schmutzigsten Flüsse Manilas. Ende offen….

Ein Teufelskreis aber wird weitergeführt.

Rory, die aufgrund ihres Überlebens bei der familiären Brandkatastrophe immer heimlich überzeugt war, für etwas Besonderes im Leben bestimmt zu sein, zieht aus dem Schicksal ihrer Schwester eine nicht erwartete Konsequenz: Sie entschließt sich, es besser als diese zu machen und ebenfalls im Ausland ihr Glück zu suchen, für ihren kleinen Neffen Nathan werde sie schon jemanden finden, der sich seiner annimmt.

Eine Pressemeldung über jährlich rund 600 in Manila ankommende Tote aus den verschiedenen Einsatzländern, belastbare offizielle Zahlen gibt es nicht, brachte Dalisay dazu, sich dieses Themas der philippinischen Diaspora anzunehmen. Dieses Buch, Dalisays zweites, ist erstmals 2008 erschienen. Es wird häufig dem Krimi-Genre zugeordnet, Dalisay selbst hatte zu Beginn die Idee, es als eine Art „schwarze Komödie“ zu schreiben. Das greift jedoch zu kurz. Im Kern handelt es sich vielmehr eine Bestandsaufnahme der sozialen Situation der Philippinen.

In einem Interview mit der mexikanischen Zeitschrift LetrasLibres Ende 2024 schildert Dalisay neben den wirtschaftlichen Gründen dieser Arbeitsmigration auch den kulturellen Kontext. Danach „opfern“ sich in vielen Familien ein oder zwei Personen und suchen sich Jobs im Ausland: „Zumindest mythologisieren wir sie so. Sie sind Märtyrer für das Wohlergehen der Familie“. Und Familie ist für die Filipinos ein sehr hoher Wert, für sie tut man alles!

Das Thema ist, nicht nur in Asien hochaktuell und bringt uns diese komplexe Thematik in einer nüchternen, manchmal aber auch sehr poetischen Sprache nahe. Das Buch thematisiert in Europa weitgehend unbekannte Aspekte und bringt uns pars por toto das Schicksal von vielen Millionen Menschen nahe.

Auch wenn nicht immer der Tod das letzte Wort hat, diese Lebensrealitäten haben viele negative Konsequenzen für die Menschen und die philippinische Gesellschaft insgesamt.

- – – – – – – – – – – –

Soledads Sister

When asked what the Philippines‘ biggest export is, Filipinos themselves often answer: “Our people!” There is a real and dramatic background to this answer. According to estimates, around 10 million of the approximately 120 million Filipinos work abroad, more than half of them women. The majority of these “overseas Filipino workers” are employed in other Asian countries, Arab countries, the US, and Canada.

Remittances from abroad are an indispensable economic factor for the Philippines, accounting for around 10% of gross domestic product (approximately US$40 billion). For many families, these payments are essential for their survival.

The price for the people is high. Fathers and mothers are separated from their children or spouses, other family members, and friends, often for years on end. Working and living conditions in many of the host countries are anything but humane. Exploitation, not to mention a modern form of slavery, is commonplace. The line between job placement and human trafficking is blurred, and many journeys are one-way trips…or return in a zinc coffin.

The novel Last Call Manila by José “Butch” Dalisay deals with this everyday reality in the Philippines.

Aurora V. Cabahug is one of those young women who sought a livelihood abroad. She returns to Manila—in a zinc coffin. However, Aurora is “lucky.” Walter, the police officer tasked with finding her family, is stunned when he reads her name. Aurora Cabahug? Rory, the singer? Wasn’t she the one he had admired the night before?

And indeed, Aurora is very much alive. Walter, secretly in love with the attractive singer, drives with her for hours to the capital Manila to pick up the coffin with the dead woman he doesn’t know, revealing her secret kilometer by kilometer.

Aurora and her older sister, like almost all Filipinos with Spanish names, Soledad (significantly: loneliness), are survivors of a family catastrophe. Nevertheless, their relationship cannot be described as particularly close: “To be honest, Soli was always more of a maid than a sister to her, and it’s difficult to miss someone who might as well have been a stain on a white wall.”

Soledad had left for Hong Kong years ago and later returned with a child. She soon left the little one alone with her sister Rory and borrowed her identity to build a professional future for herself in an Arab country. What happened to Soledad in that country remains a mystery, and no one there is interested in finding out. Unless the dead are members of the royal family or other influential figures, they are taken away after three days: “Just like that?” “Just like that.”

On the long journey to Manila, we learn a few things about the Philippines almost in passing. Whether it’s about the complex structures of deep-rooted corruption or the immense internal migration due to a lack of career prospects: “People who never really had a serious chance, who reluctantly accepted that every day you had three meals in your stomach was a good day and that anything beyond that was a blessing that had to be preserved and defended against the constant danger of being abandoned by luck.”

Or take the still-existing left-wing guerrilla movement: „Some people carried weapons that were far larger than his .38 service weapon. They were henchmen and followers of a dogged belief in—what was it again?—justice or the future or some such abstraction that never justifies another corpse with its mouth open and covered in flies, lying somewhere in a ditch.“

There is also no shortage of realistically comical scenes that reflect the Filipino mentality, such as the family that arrives too early to pick up a close relative who has been beheaded in an Arab country and then enjoys themselves at a nearby folk festival until the next day. Life is short.

Apart from the big surprise of the identity swap, there are other twists in this book that, despite all the tragedy, are more likely to make you laugh because of their absurdity. For example, the car carrying the coffin is stolen by a petty criminal and disappears with it into the brackish water of one of Manila’s dirtiest rivers. The ending is open…

But a vicious circle continues.

Rory, who, having survived the family fire disaster, had always secretly believed that she was destined for something special in life, draws an unexpected conclusion from her sister’s fate: she decides to do better than her and also seek her fortune abroad, believing that she will find someone to take care of her little nephew Nathan.

A press release about the approximately 600 dead arriving in Manila each year from various countries of employment—there are no reliable official figures—prompted Dalisay to take up the theme of the Filipino diaspora. This book, Dalisay’s second, was first published in 2008. It is often classified as a crime novel, and Dalisay herself initially had the idea of writing it as a kind of “black comedy.” However, that falls short. At its core, it is more of an assessment of the social situation in the Philippines.

In an interview with the Mexican magazine LetrasLibres at the end of 2024, Dalisay describes not only the economic reasons for this labor migration, but also the cultural context. According to her, in many families, one or two people “sacrifice” themselves and look for jobs abroad: “At least that’s how we mythologize them. They are martyrs for the well-being of the family.” And family is a very high value for Filipinos; they would do anything for it!

The topic is highly topical, not only in Asia, and presents this complex issue in a sober, but sometimes also very poetic language. The book addresses aspects that are largely unknown in Europe and gives us a glimpse into the fate of many millions of people.

Even if death does not always have the last word, these realities of life have many negative consequences for the people and Philippine society as a whole.

- – – – – – – – – – – – –

Spanische Fassung:

Cuando se les pregunta cuál es el producto estrella de exportación de Filipinas, ellos mismos suelen responder: «¡Nuestra gente!». Esta respuesta tiene un trasfondo real y dramático. Se estima que, de los aproximadamente 120 millones de filipinos, unos 10 millones, más de la mitad de ellos mujeres, trabajan en el extranjero, la mayoría de estos «trabajadores Filipinos en el exterior“ en otros países asiáticos, en países árabes, en Estados Unidos y en Canadá.

Las remesas del extranjero son un factor económico indispensable para Filipinas, ya que representan alrededor del 10 % del producto interior bruto (unos 40 000 millones de dólares estadounidenses). Para muchas familias, estos pagos constituyen una base indispensable para su supervivencia.

El precio que pagan las personas es alto. Padres y madres se separan de sus hijos o cónyuges, otros familiares y amigos, a menudo durante años. Las condiciones de trabajo y de vida en muchos de los países de acogida distan mucho de ser dignas, la explotación, por no decir una forma moderna de esclavitud, está a la orden del día, la frontera entre la colocación laboral y la trata de personas es difusa, y hay muchos viajes sin retorno… o con retorno en un ataúd de zinc.

La novela «Last Call Manila», de José «Butch» Dalisay, se centra en esta realidad cotidiana en Filipinas.

Aurora V. Cabahug es una de esas jóvenes que buscaban ganarse la vida en el extranjero. Regresa a Manila… en un ataúd de zinc. Sin embargo, Aurora tiene «suerte». Walter, el policía encargado de buscar a la familia, se queda de piedra al leer el nombre. ¿Aurora Cabahug? ¿Rory, la cantante? ¿Acaso no la había admirado la noche anterior?

Y, efectivamente, Aurora está viva y coleando. Walter, secretamente enamorado de la atractiva cantante, recorre con ella las horas de viaje hasta la capital, Manila, para recoger el ataúd con la desconocida difunta y, kilómetro a kilómetro, va desvelando su secreto.

Aurora y su hermana mayor, como casi todos los filipinos con nombre español, Soledad (significativamente: soledad), son supervivientes de una catástrofe familiar. Sin embargo, no se puede decir que su relación sea especialmente estrecha: «Para ser sinceros, Soli siempre fue más una criada que una hermana para ella, y es difícil echar de menos a alguien que podría haber sido una mancha en una pared blanca».

Soledad se había marchado a Hong Kong hacía años y había regresado más tarde con un hijo. Muy pronto dejó al pequeño solo con su hermana Rory y se apropió de su identidad para labrarse un futuro profesional en un país árabe. Se desconoce lo que le sucedió a Soledad en ese país, y a nadie le interesa. A menos que los fallecidos sean miembros de la familia real u otras personas influyentes, se los llevan al cabo de tres días: «¿Así sin más?» —«Así sin más».

En el largo camino hacia Manila, se aprende casi de pasada algunas cosas sobre Filipinas. Ya sea sobre las complejas estructuras de una corrupción profundamente arraigada, ya sea sobre la inmensa migración interna debido a la falta de perspectivas profesionales: «Personas que en realidad nunca tuvieron una oportunidad seria, que solo aceptaban a regañadientes que cada día en el que se llenaba el estómago con tres comidas era un buen día y que todo lo que iba más allá de eso era una bendición que había que conservar y defender del peligro constante de que la suerte les abandonara».

O sobre la guerrilla de izquierda que aún existe: «Algunas personas portaban armas mucho más grandes que su arma reglamentaria del calibre 38. Eran secuaces y seguidores de una fe obstinada en… ¿qué era? ¿La justicia o el futuro o alguna abstracción que nunca justifica otro cadáver con la boca abierta y cubierto de moscas en alguna zanja?».

Tampoco faltan escenas realmente cómicas que reflejan la mentalidad de los filipinos, como la familia que llega demasiado pronto a recoger a un pariente cercano decapitado en un país árabe y luego se divierte hasta el día siguiente en una feria cercana. La vida es corta.

Aparte de la gran sorpresa del intercambio de identidades, hay otros giros en este libro que, a pesar de toda su tragedia, vuelven a ser más bien cómicos por su absurdo. Así, el coche con el ataúd es robado por un delincuente de poca monta y desaparece con él en las aguas salobres de uno de los ríos más sucios de Manila. Final abierto…

Pero el círculo vicioso continúa.

Rory, que debido a su supervivencia en el incendio familiar siempre estuvo secretamente convencida de que estaba destinada a algo especial en la vida, saca una conclusión inesperada del destino de su hermana: decide hacerlo mejor que ella y también buscar su suerte en el extranjero, ya que encontrará a alguien que se haga cargo de su pequeño sobrino Nathan.

Una noticia de prensa sobre los aproximadamente 600 cadáveres que llegan cada año a Manila procedentes de los distintos países de destino, no hay cifras oficiales fiables, llevó a Dalisay a abordar este tema de la diáspora filipina. Este libro, el segundo de Dalisay, se publicó por primera vez en 2008. A menudo se clasifica dentro del género policíaco, ya que la propia Dalisay tuvo inicialmente la idea de escribirlo como una especie de «comedia negra». Sin embargo, esto se queda corto. En esencia, se trata más bien de un análisis de la situación social de Filipinas.

En una entrevista con la revista mexicana LetrasLibres a finales de 2024, Dalisay describe, además de las razones económicas de esta migración laboral, el contexto cultural. Según él, en muchas familias una o dos personas se «sacrifican» y buscan trabajo en el extranjero: «Al menos así es como los mitificamos. Son mártires por el bienestar de la familia». Y la familia es un valor muy importante para los filipinos, ¡por ella se hace cualquier cosa!

El tema es de gran actualidad, no solo en Asia, y nos acerca a esta compleja problemática con un lenguaje sobrio, pero a veces también muy poético. El libro aborda aspectos en gran medida desconocidos en Europa y nos acerca, pars pro toto, al destino de muchos millones de personas.

Aunque la muerte no siempre tiene la última palabra, estas realidades de la vida tienen muchas consecuencias negativas para las personas y para la sociedad filipina en su conjunto.

#philippinen #buchmesse

#philippinesfrankfurt2025

#josedalisay #transitverlag

#nicofröba #overseasworker #anvilpublishung

#editorialpre-textos #tbr #bookstagram